An attractive reissue:

Littleton Powys: The Joy of It

Limited edition Hardback

with coloured endpapers and silk ribbon marker

256pp ISBN: 9781908274045 The Sundial Press.

From the introduction by Peter Tait:

Littleton listed six reasons why, in the end, he decided to write about his life: to correct any errant impressions

of his home, his family and his brothers; to express his thankfulness for his remarkably happy life; to provide a comparison for the reader with the remarkable Autobiography of

his brother, John Cowper, with whom, in spite of all their differences, he had been ‘bound together by the closest ties of friendship for over sixty years’; as a tribute to the people and places that had afforded him so much happiness; to pass on his experiences as a headmaster; and finally, to express the debt he owed to nature for his happiness. In the course

of the book, he accomplishes each task in turn.

The Joy of It is a celebration of a life well-lived, covering the first sixty-three years of

Littleton’s life from his childhood at Shirley and Montacute, through his time as a pupil at Sherborne, to his

working life at Bruton, Llandovery and Sherborne and the first fifteen years of his retirement. The first chapter, which precedes his own birth and early childhood in the book’s chronology, is an exaltation of nature and sets the tone for the remainder of the book, epitomising Littleton’s philosophy of life, his quest for happiness and his

exhortation to ‘rejoice, rejoice, in all things, rejoice.’

A Review of The Joy of It

.jpg) Among the various autobiographical writings of the Powys family, Littleton Powys’s The Joy of It tends to be the most overlooked. One obvious reason is that Littleton was not a ‘writer’ and left no significant body of literary work that would

attract a readership or otherwise compel attention. Perhaps another is that he was not interested in the sort of self-mythologising and shape-shifting at which his brothers were so adept, as evidenced in John Cowper’s Autobiography,

Theodore’s Soliloquies of a Hermit and Llewelyn’s Skin for Skin (and

just about everything else). Littleton spoke, and spoke out, plainly and

inoffensively, and precisely for this reason The Joy of It is an invaluable

text to gaining a fuller understanding of the Powys family, and as a balance,

if not corrective, to some of the views not only of John and Llewelyn but of

early Powys biographers like Heron Ward and Louis Wilkinson.

Among the various autobiographical writings of the Powys family, Littleton Powys’s The Joy of It tends to be the most overlooked. One obvious reason is that Littleton was not a ‘writer’ and left no significant body of literary work that would

attract a readership or otherwise compel attention. Perhaps another is that he was not interested in the sort of self-mythologising and shape-shifting at which his brothers were so adept, as evidenced in John Cowper’s Autobiography,

Theodore’s Soliloquies of a Hermit and Llewelyn’s Skin for Skin (and

just about everything else). Littleton spoke, and spoke out, plainly and

inoffensively, and precisely for this reason The Joy of It is an invaluable

text to gaining a fuller understanding of the Powys family, and as a balance,

if not corrective, to some of the views not only of John and Llewelyn but of

early Powys biographers like Heron Ward and Louis Wilkinson.

Indeed,

among the half-dozen reasons Littleton gives in his Preface for writing these

memoirs are to counter comments in the press and other books that he felt

distorted the truth about his parents and siblings, and to compare his own

temperament specifically with that of his elder brother as expressed in

Autobiography. He was especially close to John, despite the latter’s

secretiveness in certain matters relating to his personal life, from their

shared childhood and schooldays to the Norfolk trip they made in their late

fifties, and into their old age when Littleton would visit John in Wales. The

divergence in their lifestyles was really set in train at Cambridge, where, as

Littleton wrote, ‘John’s ways were not my ways, nor his thoughts my thoughts,

nor (with two or three exceptions) his friends my friends.’ From university

Littleton, unlike his brother, went on to become a pillar of the community, and

if in consequence he was occasionally the butt of family humour, it’s worth

remembering that without their pillars communities tend to collapse. It is not

difficult to see why he was his father’s favourite or why John addressed him as

‘Best of the sons’: in addition to his sense of public duty, Littleton

displayed a familial responsibility not always in evidence in some of his

siblings, often coming to their financial rescue.

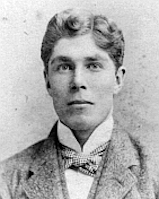

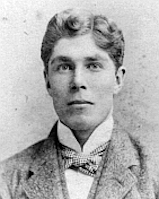

The

frequent designation of Littleton as the most ‘conventional’ of the brothers

brings with it a suggestion of dullness. Littleton was anything but dull. In

appearance he was strikingly handsome, always elegantly dressed and with a

flower in his buttonhole, and his deep clear voice was put to especially good

effect when he read the lessons in Sherborne Abbey. If that was all there was

to him he would hardly have attracted in his late sixties the attentions of the

young Elizabeth Myers, who at half his age became his second wife. But as she

noted: ‘Littleton never fails to tell you something interesting about life and

the world. Every conversation with him extends the horizon of your mind.’ It is

our loss that Littleton’s forte was conversation rather than literary

creativity; in particular, his knowledge of botany and ornithology, abundantly

evident in his book, probably surpassed that of anyone in the family.

Littleton’s

views and lifestyle were antithetical to those of the family friend and bon

viveur Louis Wilkinson, and there was often an undercurrent of tension between

them. Littleton had objected to certain parts of Louis’s Swan’s Milk and

this tension was probably exacerbated by Welsh Ambassadors, which

appeared in 1936 and in which Littleton, as Llewelyn thought at least, came off

badly. ‘The book does outrage to the ethos of his circle,’ Llewelyn wrote to

Louis, ‘and he will dislike being in any way involved with it.’ But he shortly

mentioned also that Katie had told him Littleton did not seem at all personally

disturbed by the book. Perhaps he was already writing his riposte, for in

August that year Llewelyn told Louis that Littleton was reading his

autobiography to him, and passed a judgement that stands the test of time: ‘It

is unexpectedly good – rational, unaffected, charming – objective and

unintellectual. I think it will be mightily appreciated by many readers.’

Littleton’s

views and lifestyle were antithetical to those of the family friend and bon

viveur Louis Wilkinson, and there was often an undercurrent of tension between

them. Littleton had objected to certain parts of Louis’s Swan’s Milk and

this tension was probably exacerbated by Welsh Ambassadors, which

appeared in 1936 and in which Littleton, as Llewelyn thought at least, came off

badly. ‘The book does outrage to the ethos of his circle,’ Llewelyn wrote to

Louis, ‘and he will dislike being in any way involved with it.’ But he shortly

mentioned also that Katie had told him Littleton did not seem at all personally

disturbed by the book. Perhaps he was already writing his riposte, for in

August that year Llewelyn told Louis that Littleton was reading his

autobiography to him, and passed a judgement that stands the test of time: ‘It

is unexpectedly good – rational, unaffected, charming – objective and

unintellectual. I think it will be mightily appreciated by many readers.’

Littleton and Louis were to meet six months later, in February 1937, when Gertrude Powys

had a showing of her works in London. Louis immediately wrote to Llewelyn:

‘Littleton was charming to me at Gertrude’s Private View. He talked with me in

the most friendly manner, and at parting held my hand and pressed it to his

side. I was delighted & amazed. What magnanimity!’ All the Powyses had

magnanimity, but Littleton had it in spades and it’s one of the many qualities

that shine through in The Joy of It. Another is gratitude for his own

happy life and for the glories of Nature. In many ways Littleton’s is a deeply

religious book, though not indeed in any conventional sense. Not long before

his death he wrote to Ichiro Hara, ‘“He findeth GOD, who finds the Earth He

made” is the background of my Faith’ – and it had always been so. ‘He was a

lover of life,’ Oliver Holt wrote of him. ‘To have been born into the world at

all – a world so full of radiant and manifold beauties – he regarded as an immeasurable

privilege, and his whole life was an unbroken act of praise.’

The world evoked in The Joy of It – of gentlemanly conduct and fair play, of

individual responsibility, of a largely benevolent Nature – may seem sadly

remote in an age when we are constantly encouraged to believe that Britain is

‘broken’ (a view Littleton himself would have given short shrift). But that

world is not entirely gone. There are still good schools, there are still

well-mannered people, there are still natural beauties in abundance. What seems

to be rarer these days is an attitude – the shameless capacity for simple

delight that Littleton, like all the Powys siblings, possessed, and that makes

his book all the more remarkable.

This new hand-numbered limited edition of The Joy of It, the work’s first

republication in hardback, is significant for several reasons. It corrects

certain misprints, errors and solecisms in the first edition; it has a

perceptive and informative introduction by the current Sherborne Prep

headmaster Peter Tait; it is beautifully designed and produced, with coloured

endpapers and marker ribbon; and its striking blue dust jacket is a perfect

frame for the wonderful portrait of Littleton by Gertrude Powys that adorns the

cover and which, as far as I know, has itself never before been published. It

seems unlikely that The Joy of It will ever again be reissued, but

certainly not in an edition as distinguished as this, a true collector’s item.

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a book like this even being written today, a memoir

which celebrates childhood and schooldays, family and friendships, and Nature

above all – and all without a trace of cynicism or bitterness or self-pity.

Littleton maintained his feelings of gratitude even in bereavement with the

loss of his first wife Mabel Bennett from cancer and then of Elizabeth Myers

from tuberculosis, and when illness and age set in during his last painful

years.

Typical of the many incidental but movingly evocative revelations in the book is when

Littleton relates how on recently opening his schoolboy copy of Horace’s Odes

he noted what he had written in the margin nearly half a century earlier:

‘Powys minor, and a happy life is his.’ The Joy of It is a record of one

man’s enduring gratitude for that life and happiness, and it is this quality

more than any other that gives this engaging work its distinctive charm.

Whether he was Mr Powys, headmaster of Sherborne Prep, or ‘Tom’ to his

siblings, or ‘Owen’ in his old pupil Louis MacNeice’s 'Autumn Sequel',

‘Rejoice, rejoice’ was always Littleton’s motto: '…on two sticks/ He

still repeats it, still confirms his choice/ To love the world he lives in.’ The

evidence of that love is abundant in The Joy of It and this superb new

edition constitutes a fitting tribute to its author and, through him, to the

whole Powys family.

Anthony Head

The Powys Society Newsletter 71, November 2010

Littleton Charles Powys (1874–1955) was the second eldest of eleven children in a uniquely precocious family, one of the most significant in the cultural history of Britain, of whom the writers John Cowper Powys, T. F. Powys and

Llewelyn

Powys are the most famous.

Littleton Charles Powys (1874–1955) was the second eldest of eleven children in a uniquely precocious family, one of the most significant in the cultural history of Britain, of whom the writers John Cowper Powys, T. F. Powys and

Llewelyn

Powys are the most famous.

.jpg) Among the various autobiographical writings of the Powys family, Littleton Powys’s The Joy of It tends to be the most overlooked. One obvious reason is that Littleton was not a ‘writer’ and left no significant body of literary work that would

attract a readership or otherwise compel attention. Perhaps another is that he was not interested in the sort of self-mythologising and shape-shifting at which his brothers were so adept, as evidenced in John Cowper’s Autobiography,

Theodore’s Soliloquies of a Hermit and Llewelyn’s Skin for Skin (and

just about everything else). Littleton spoke, and spoke out, plainly and

inoffensively, and precisely for this reason The Joy of It is an invaluable

text to gaining a fuller understanding of the Powys family, and as a balance,

if not corrective, to some of the views not only of John and Llewelyn but of

early Powys biographers like Heron Ward and Louis Wilkinson.

Among the various autobiographical writings of the Powys family, Littleton Powys’s The Joy of It tends to be the most overlooked. One obvious reason is that Littleton was not a ‘writer’ and left no significant body of literary work that would

attract a readership or otherwise compel attention. Perhaps another is that he was not interested in the sort of self-mythologising and shape-shifting at which his brothers were so adept, as evidenced in John Cowper’s Autobiography,

Theodore’s Soliloquies of a Hermit and Llewelyn’s Skin for Skin (and

just about everything else). Littleton spoke, and spoke out, plainly and

inoffensively, and precisely for this reason The Joy of It is an invaluable

text to gaining a fuller understanding of the Powys family, and as a balance,

if not corrective, to some of the views not only of John and Llewelyn but of

early Powys biographers like Heron Ward and Louis Wilkinson.  Littleton’s

views and lifestyle were antithetical to those of the family friend and bon

viveur Louis Wilkinson, and there was often an undercurrent of tension between

them. Littleton had objected to certain parts of Louis’s Swan’s Milk and

this tension was probably exacerbated by Welsh Ambassadors, which

appeared in 1936 and in which Littleton, as Llewelyn thought at least, came off

badly. ‘The book does outrage to the ethos of his circle,’ Llewelyn wrote to

Louis, ‘and he will dislike being in any way involved with it.’ But he shortly

mentioned also that Katie had told him Littleton did not seem at all personally

disturbed by the book. Perhaps he was already writing his riposte, for in

August that year Llewelyn told Louis that Littleton was reading his

autobiography to him, and passed a judgement that stands the test of time: ‘It

is unexpectedly good – rational, unaffected, charming – objective and

unintellectual. I think it will be mightily appreciated by many readers.’

Littleton’s

views and lifestyle were antithetical to those of the family friend and bon

viveur Louis Wilkinson, and there was often an undercurrent of tension between

them. Littleton had objected to certain parts of Louis’s Swan’s Milk and

this tension was probably exacerbated by Welsh Ambassadors, which

appeared in 1936 and in which Littleton, as Llewelyn thought at least, came off

badly. ‘The book does outrage to the ethos of his circle,’ Llewelyn wrote to

Louis, ‘and he will dislike being in any way involved with it.’ But he shortly

mentioned also that Katie had told him Littleton did not seem at all personally

disturbed by the book. Perhaps he was already writing his riposte, for in

August that year Llewelyn told Louis that Littleton was reading his

autobiography to him, and passed a judgement that stands the test of time: ‘It

is unexpectedly good – rational, unaffected, charming – objective and

unintellectual. I think it will be mightily appreciated by many readers.’